#GeekingOutSeries/Safety101/ExpellarmusPathogenus/2

This post is part of the Geeking Out series which presents data-driven information on food and farming, safety in the kitchen, practical science for cooks, cooking techniques and processes and other relevant nerdy stuff that every cook should know. For the next few weeks, we will be covering topics from the chapter, Safety 101.

In part 1 of “Expellarmus Pathogenus!” Understanding Pathogens, I gave a broad overview of Pathogens so we can all be on the same page with basic Hygiene and Sanitation rules.

In this installment of “Expellarmus Pathogenus”, we’ll talk about how to kill or minimize these disease-causing microorganisms and why your fridge deserves more respect. I’ll summarize the rules from both parts of the article at the end.

Let’s Kill them pathogens!

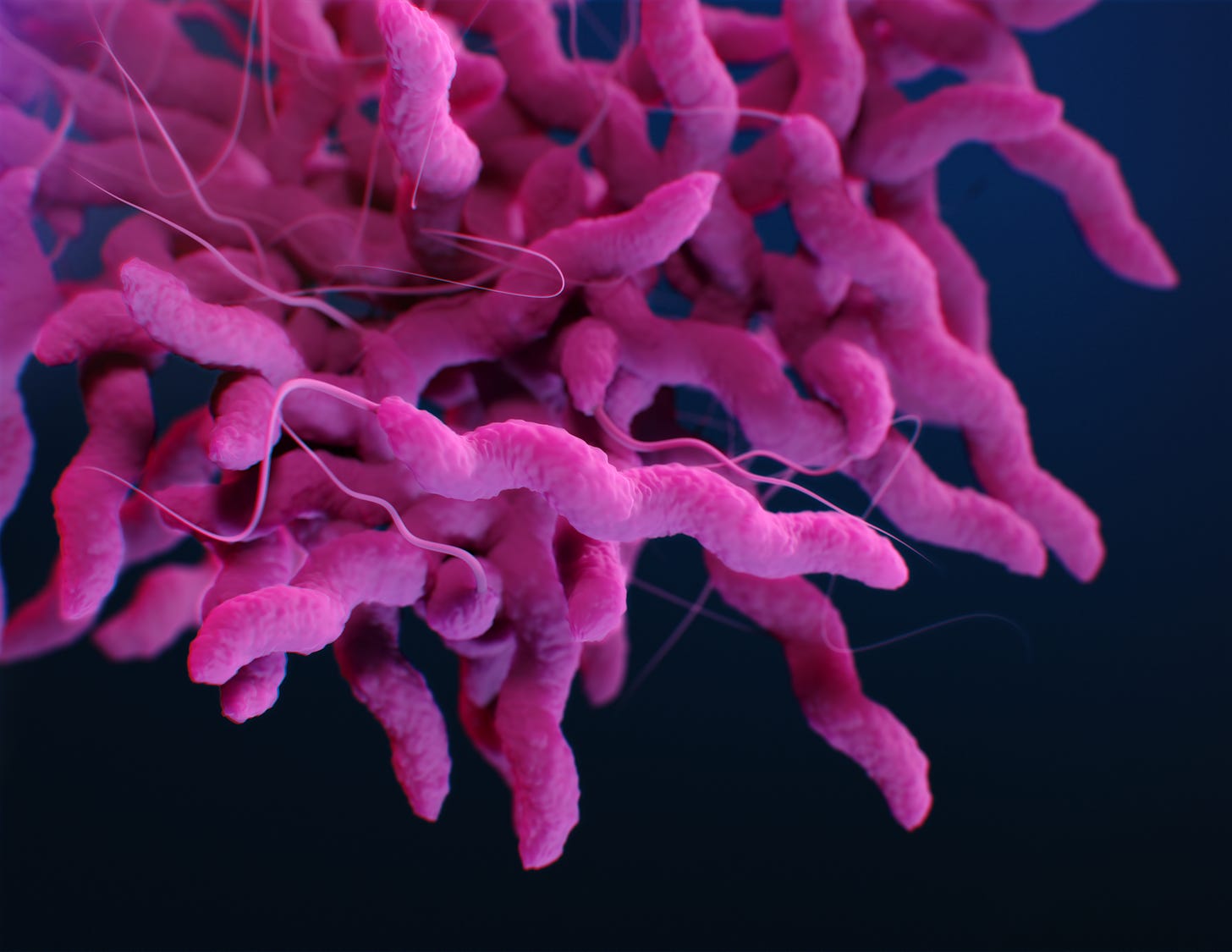

When we talk about foodborne pathogens, bacteria and viruses often come to mind, but these are just a few of the microorganisms that can make us sick. Parasites, fungi (yeast and mold), protozoa are also pathogens that make their way into our kitchens. With the exception of the Norovirus, the most common foodborne pathogens in the US are bacteria such as Salmonella, Clostridium Perfringens, Campylobacter, Staphylococcus, E.Coli and Listeria. If you’ve never heard of them before, that’s totally okay. Some are new to me as well. What matters is you know they’re in food and more importantly, that you learn how to make your food safe. The good news is, all of them, including the virus Norovirus, can be killed or rendered inactive at certain temperatures.

Temperature control is just one way we manage our pathogen levels and probably the easiest to control. There are other contributing factors such as moisture, air, acidity, light, which we’ll talk about in future posts. As it turns out, it’s fairly easy to make our foods safe from the most common foodborne pathogens, and it involves the pleasant activity of cooking.

Earlier we said that pathogens reside in our raw food, especially in animals. This is exacerbated by unhygienic and cruel farm practices, such as housing livestock in Concentrated Animal Feeding Operations (CAFOs), active breeding grounds for pathogens. Remember the cesspool of feces? Pathogens in our animals is why consuming raw or undercooked poultry, meat and shellfish is among the leading causes of foodborne illnesses, or what we call food poisoning. Cooking to the right temperature remains the most effective way of killing these disease-causing pathogens.

Here are the recommended minimum internal temperatures needed to safely cook our meats, poultry and seafood. Note that internal temperature is different from the temperature you cook your food at. To measure internal temperature, you will need a thermometer. You can check the full list from the USDA Food Safety and Inspection service site.

Ground Meat and Meat mixtures: 165°F for chicken and turkey; 160°F for all others

Poultry: 165°F

Beef, Pork, Veal, Lamb, Fish: 145°F

Rest time for Meats (not poultry): 3 minutes

Rest time refers to the time necessary for food to sit before cutting and consuming, because temperatures fluctuate during the rest period. Resting is also recommended from a culinary standpoint, because slicing meat/poultry too soon will cause valuable juices to leak out.

Okay, first let me say that what I just mentioned are official USDA guidelines. It is necessary to give this as a basis before discussing exceptions, because from the gustatory standpoint of taste, mouth feel, and other markers of deliciousness, absolute safety is not always the prime concern to the mad chef, or diner, for that matter. Why dishes like wild fugu- the poisonous puffer fish that’s a delicacy in Japan, or Casu Marzu, a Sardinian cheese infested with maggots make it to anyone’s table could perhaps be attributed to rarified taste buds and perhaps a proclivity towards danger. For those of us outside of cultures that prize such dishes, it seems tantamount to playing Russian roulette with your life, if not your general well-being. Then again, my favorite dish as a child was Steak Tartare, raw ground beef that used to be served in fancier restaurants a long time ago, and which has all but disappeared today.

This overview on pathogens is to give you a starting point on understanding dangers that are part of the cooking process. When we are more informed, we’re in a better position to calculate the risks should we decide to deviate from the rules. I love sashimi and sushi, for instance and understand that parasites can pose a risk eating raw fish. So I only consume these from reputable sources and should I be preparing it myself, to only purchase sashimi or sushi-grade fish, which has nothing to do with any special process or divination, according to this article on Serious Eats, just that the processor has deemed it safe to eat a particular fish raw. So it will come down to, do you trust your fishmonger? And on that note, you really should be thinking twice about buying sushi from local convenience stores.

Another common deviation from the internal temperature rule is what many gourmets consider the best way of preparing steak, and that is, medium rare to medium, temperatures which range from 129°F - 135°F, which is lower than the USDA guideline of 145°F. Steaks cooked to this temperature are moist and have great mouth feel and flavor. To reduce the incidence of pathogens in meat, I only purchase from butchers and stores that don’t source from farms that have their animals in CAFOs.

Rule-bending is not something I normally advocate to those new to the kitchen. There is a reason why there are official guidelines in the first place. For public safety, rules need to be concise, easy to understand and to account for the worst possible conditions, even the uneven temperaments and habits of cooks who don’t follow basic hygiene and sanitation procedures. Official guidelines tend to be conservative; a prudent stance, if not the most delicious. For an interesting account on the origins of food safety rules from the perspective of writers who argue against overcooking, check out this article from The Scientific American.

In the interest of precision, I did some digging. The actual temperatures that kill most bacteria according to the World Health Organization is at 149°F-- below the 165°F recommended internal temperatures for poultry and ground meat. All the pathogens I mentioned earlier are killed at 149°F except for Norovirus, Clostridium Perfringens and most strains of Staphylococcus, which only require 140°F, although a few variants of Staphylococcus are more heat-resistant, but these are rare. Parasites are killed between temperatures 140-160°F. So there are already many inconsistencies in the official guidelines which by its own standards, leads to overcooking poultry and undercooking meats and seafood.

Now if you’re worried you’d be glued to a food thermometer every time you cook, I want to reassure you that doesn’t have to be the case. While a food thermometer is the most accurate method of determining food temperature, there are many ways to tell a dish is sufficiently cooked. Be advised that some of what I mention may deviate from the USDA guidelines on internal temperatures, and are given more in consideration of gastronomic value and calculated safety risks where sanitation and hygiene rules are observed and food is procured from trusted sources. Here are some examples on what to look for:

Chicken: flesh is opaque; only clear fluid (no blood) is released when prod with knife or fork

Shrimp/squid: flesh is opaque and firm; when overcooked, this becomes rubbery

Fish: flesh is opaque and flakes when you prod with knife or fork (flaking is when flesh fans out)

Mussels/Clams: shells open when cooked (note: only cook mussels/clams with intact and closed shells; discard if they are open or damaged prior to cooking)

Beef/Lamb: medium-rare or medium is often recommended for flavor, moisture and over-all quality, which allows for pink flesh to even a few drops of blood.

Pork: inside flesh is pink but no blood; outer flesh is brown

Ground Meat: brown all over; only clear fluid is released

A few other things to consider:

Bone-in meats and seafood will cook longer than boneless; So do larger or whole meats and seafood, compared to cut up pieces.

To gauge whether food is close to being cooked, it’s a good idea to check areas that are likely to cook the longest, which would be near the bone for meats and poultry. If working with pieces of varying sizes such as a fish fillet whose middle tends to be thicker than the sides, check the thickest part for done-ness.

Ground meats, due to more surface area contamination, tend to have more pathogens than other cuts and must always be fully cooked through.

Prodding and slicing to check for done-ness cause valuable juices to be released. To avoid drying out your food items, keep the slicing and cutting to a minimum

Food continues to cook when removed from the heat source and allowed to rest; though the USDA guideline is at 3 minutes, I tend to let meats rest for 5-10 minutes before cutting, especially for larger cuts. Larger masses retain more heat and internal temperatures will continue to fluctuate for much longer than 3 minutes.

Though much cooking can be done without a thermometer, you’ll need to keep it handy because there will be times you’ll need it, such as when Thanksgiving rolls around and you’re elected to roast the family turkey. I also use the thermometer for thick or large pieces of meats and poultry and generally for items that go in the oven (with an alarm that informs me when I’ve hit the desired temperature).

Rule number five: Cook food understanding the safety guidelines given on internal temperatures

The Danger Zone and Why your fridge deserves more respect

Bacteria like moisture and thrive in temperatures ranging 40 °F - 140 °F, what the USDA refers to as the Danger Zone. Keep in mind that room temperature for most of us falls smack in this range, which means perishable foods must be refrigerated and refrigerators should be cooler than the Danger Zone but not too cold to freeze, ideally between 35° F - 38 °F.

Rule number six: The Danger Zone rule— Do not leave food out of refrigeration for more than 2 hours; on a hot day (90°F or higher) reduce that to an hour.

What that means in practice is, refrigerate leftovers within the time guideline; be wary of food that sits all day in party buffets; don’t let your raw meats, poultry and seafood sit out too long before you cook them. There are exceptions to the rule of course, but that’s for another day.

Here’s a brief summary of “Expellarmus Pathogenus!” Understanding Pathogens and the basic safety rules to follow. I’ve also noted my personal practices where applicable.

Pathogens that can make people sick are everywhere. To keep you and your family safe from food-borne illnesses, follow these rules:

1. Wash your hands! And by that, I mean with soap and water. The CDC recommends at least 20 seconds. Wash your hands after using the restroom, after blowing your nose, coughing or sneezing into hands, handling sick persons, before handling food of any kind, after and while handling raw food—especially raw meat and eggs. Wash before eating. When in doubt, wash your hands.

My personal practice: To avoid drying my hands from frequent hand washing, I often use re-usable food service gloves when I work in the kitchen.

2. Wash (or dispose of, in the case of used paper towels and meat packaging) anything and everything that was in contact with raw meat, poultry, seafood and eggs.

3. Do not wash raw meat, poultry, seafood and eggs. If you do, then go to rules number one and two.

4. Buy and consume fresh vegetables and fruits and rinse, even if organic or triple washed

5. Cook food understanding the safety guidelines given on internal temperatures

My personal practice: I often take a calculated risk using gustatory guidelines with information and experience to guide me. For most stove-top cooking, I use visual and tactile cues to know when food is done. For large pieces of meat or poultry and especially if using an oven or grill, I use a thermometer.

6. The Danger Zone rule-- Do not leave food out of refrigeration for more than 2 hours; on a hot day ( 90°F or higher) reduce that to an hour.

My personal practice: There are exceptions to this rule which will be discussed when I talk about food storage and pantries. Knowing these exceptions allow me occasional flexibility, though in general it’s a rule I follow.

Additional References:

https://www.foodsafety-experts.com/food-safety/norovirus

https://www.efsa.europa.eu/en/topics/topic/listeria

https://food.unl.edu/clostridium-perfringens

https://ohioline.osu.edu/factsheet/HYG-5564-11

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0924224418301560

https://www.cdc.gov/media/subtopic/images.htm

"Expellarmus Pathogenus!" Understanding Pathogens (part 2)